While countries in Latin America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania account for the majority of murders and threats against environmental defenders, donors still hesitate to fund comprehensive protection networks

By Gabi Coelho

Translated by Diego Lopes/Verso Tradutores

The 30th United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) is the third COP that environmental activist Precious Kalombwana 33, has attended. As she walks through the hot corridors of the Green Zone in Belém, weather alerts notify her cell phone: continuous heavy rain with storm forecasts in the Mumbwa area, a city in the central district of Zambia, in Central Africa, where she lives.

Kalombwana knows the power of the storms: “As a child, I didn’t fully understand what deforestation meant, but I felt the change. The rains became unpredictable, the streams dried up, and one year, the floods swept away our house,” she says. “I still remember my father’s face when we lost everything.”

Today, as head of the Citizens Network for Community Development Zambia, a non-governmental organization focused on promoting youth and community participation in the country’s development, Kalombwana is one of the most active voices for climate justice and foreign debt cancellation in her region. According to her, these debts are suffocating her country and preventing basic investments in health, education, and adaptation to climate crises. “I realized that climate change is not something distant—it is real, personal, and affects the poorest first.”

The price of environmental protection

From the Amazon to the Miombo forest—a protected area that stretches across much of the southern tip of the African continent and the central region—the pattern is the same: environmental defenders face persecution, threats, and criminalization, when they should be protected.

In April 2024, Kalombwana was arrested in Washington DC, in the United States, during a protest at the International Monetary Fund’s spring meetings. In August, she confronted a Zambian government bill that sought to limit the activities of NGOs—an initiative that was blocked after strong mobilization by civil society. In both episodes, she was alone: without a salary, legal support, or insurance.

According to the report Global Analysis 2024/25, by Front Line Defenders, 8.5% of violations against human rights defenders are related to environmental issues in Africa. The most common forms are threats and harassment (17.1%), death threats (14.3%), arbitrary arrests (14%), surveillance (12.1%), and physical attacks (8.3%).

“I received direct threats and was arrested. But silence is not an option when your people suffer,” she says. Her organization works with rural communities where the impact of climate change is most severe—and where international funding rarely arrives. It’s an individual facing off against billionaire corporations .

Kalombwana advocates for new legislation that would require private creditors to forgive the debts of countries facing a climate crisis. For her, climate justice demands a clear equation: without debt relief, there is no way to finance adaptation; without protection for activists, there is no one to push for structural changes; and without direct funding to grassroots organizations, they continue to operate based on “passion”—a word she uses without romanticizing it.

“The resources go to large NGOs in the capital cities. We need support that reaches the villages—legal assistance, emergency funds, mental health support,” she argues.

Congolese environmental lawyer and activist Oliver Ndoole also works in his territory defending environmental rights, which he understands as synonymous with the right to life. “When we talk about environmental rights, we are talking about human rights, linked to our stability and our entire social economy,” he states.

Current executive secretary of the Congolese Alert for the Environment and Human Rights, Ndoole emphasizes that funding comprehensive protection for activists should be the first step towards philanthropy allied with the environmental struggle. “When protection is lacking, the entire social ecosystem of our community is affected,” argues the activist, “When I was imprisoned in Uganda because of my work, my whole family was affected.”

The defunding scenario

The criticisms from Kalombwana and Ndoole resonate in Brazil, host of COP30. According to Alexandre Pacheco, a lawyer, historian, and manager of the Defenders of the Fundo Brasil program, foundations attempting to support initiatives in this field face “great difficulty in raising funds for protection and security.”

Fundo Brasil is one of the organizations invited to the panel “Climate Justice and Defenders: Financing for the Protection of Life and Territories”, which takes place this Monday (17), at The Global South House.

According to Pacheco, this difficulty is “a reflection of an international understanding that has gained ground in the field of philanthropy, that after the 2022 election, with the defeat of a candidate with authoritarian leanings, there would be a full return of the democratic field to Brazil and that this would have ended the emergency situations.”

However, the data shows a different reality. The report On the Front Line — Violence against Human Rights Defenders in Brazil (2023–2024), produced by the organizations Justiça Global and Terra de Direitos, shows that every 36 hours a person suffers violence for working in the defense of human rights in the country — and 80.9% of these violations affect those who protect the environment and territories.

The study mapped 318 episodes of violence that resulted in 486 victims, including individuals and groups. In the first two years of the current government alone, between 2023 and 2024, 55 murders, 96 attempted murders, 175 threats, and 120 episodes of criminalization were identified.

According to Pacheco, “violence has returned from a different perspective, because until 2022 and 2023 it had one profile—now it has a much more violent profile,” in an attempt to block the mobilization and progress “of social movements, collectives, and communities.”

“Since at least 2014, these forces have been advancing territorially,” he continues. “The elections of recent years have demonstrated an advance of conservative forces. So, the reality we have in the territory is one of increased violence. But from an international perspective, there is an interpretation that the violence and emergencies have ended.”

Territory as the soul of politics

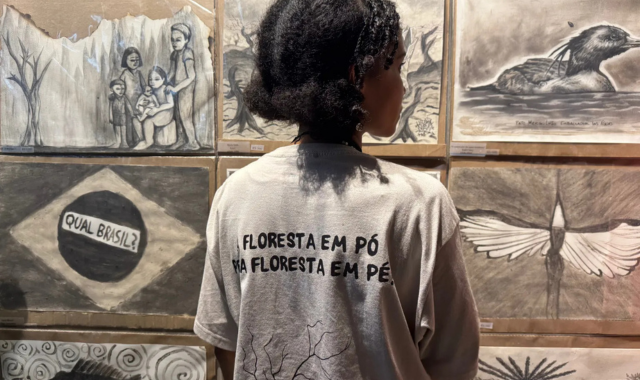

The discrepancy between the actual violence in the territories and the international perception that the emergencies have ended has concrete—and lethal—consequences. In Nova Ipixuna, in southeastern Pará, the impunity for a 2011 environmental crime illustrates how the lack of structural protection for environmental defenders is not only about preventing new violence, but also about ensuring justice for the violence that has already occurred.

On May 24, 2011, the extractive couple Zé Cláudio Ribeiro da Silva, 52, and Maria do Espírito Santo, 51, were executed in an ambush with shotgun fire in the Praialta Piranheira Agro-extractive Settlement Project. Recognized leaders in the defense of the forest, both had publicly denounced land grabbing schemes and illegal logging in the region.

Fourteen years later, the trial of those who ordered the killing has still not taken place. Two perpetrators were convicted in 2013, but those intellectually responsible for the assassination remain unpunished while the case drags on in the courts. Family members and fellow activists created the Zé Cláudio and Maria Institute, focused on protecting environmental defenders.

The institute’s actions take place in a worrying scenario: Latin America has been, for years, the most dangerous region in the world for those who defend forests, rivers, Indigenous territories, and the climate. A Front Line Defenders report confirms the pattern: in the Americas, the most reported violations against defenders are legal actions (32.5%), threats and harassment (14.6%), physical attacks (9.9%), and arbitrary arrest (7.9%). Brazil, Colombia, Honduras, Ecuador, Mexico, Guatemala, and Peru are among the most dangerous countries for those working in the defense of human and environmental rights.

Colombia leads the global ranking of assassinations of human rights defenders. In 2024, 157 social leaders and human rights defenders were killed in the country, according to the Somos Defensores Program—almost half of all documented assassinations worldwide that year. This number is more than ten times higher than that of Brazil, which recorded 15 defenders murdered in the same period.

Creator of the Life of Pachamama project, Juan David Amaya came from Colombia to COP30 and questions the allocation of philanthropic resources to environmental causes. For him, investing in young people in the fight for climate justice should be considered now, not in the long term. “Less than 1% of global climate finance goes to youth,” he points out, “we are the future and we are also the present; to promote this change in the crisis we are currently experiencing, we need support that allows us to elevate our proposals and initiatives.”

Protection that goes beyond mere words

A global initiative was launched during COP30. The LEAD (Lighthouse Environmental Action for Defenders) initiative, promoted by Global Witness, brings together governments, environmental human rights defenders, civil society leaders, UN agencies and institutions to address three main areas: ensuring recognition for defenders, strengthening their meaningful participation in multilateral decision-making spaces.

The opening was led by Claudelice Santos, head of the Zé Maria Institute, who highlighted the essential role of environmental defenders and invited Sonia Guajajara, Minister of Indigenous Peoples; Anielle Franco, Minister of Racial Equality; and Joan Carling, director of Indigenous Peoples Rights International (IPRI) and Filipino defender.

Carling stated that “the initiative was not born in a meeting room, but rather from territories and struggles. People like Claudelice Santos, who lost family members in environmental conflicts in the Brazilian Amazon, or the young leader Juan Amaya, who defends indigenous territorial rights in Colombia, have stories of resistance that are the basis of LEAD.”

“It is not enough to symbolically recognize the defenders. What we demand—and deserve—are guarantees of their safety, their inclusion in decision-making spaces, and effective accountability for the threats and crimes committed against them. “Today’s launch sends a powerful message of global solidarity, but what matters most is what happens next,” Carling added .

For Pacheco, from the Fundo Brasil, this protection is a condition for any progress. “The threat has the power to paralyze political action,” he states. “There are structural issues that will not advance if we do not keep human rights defenders protected.”

The manager emphasizes that the violence is not only physical. “It’s impossible to deny today the impact of the threats and risks experienced on the mental health of those who are part of community organizations,” he points out. “At Fundo Brasil, we have a huge percentage of emergency cases that require some level of psychosocial protection—whether it’s medication, care, therapy, or support groups. There’s a range of demands from the community that demonstrate how necessary this is.”

For this protection to work, it is essential that international funding engages with those on the ground. “Philanthropy, especially international philanthropy, needs to create communication tools that are closer to philanthropy at the local level,” argues Pacheco. Only then will it be possible to structure strategies that are truly effective.

“The need is to rethink protection, not exclusively in the sense of physical protection or exclusively digital protection, but to think of protection as a way to build political action in a healthy environment,” concludes Pacheco. “Thinking about comprehensive protection, about comprehensive security, is understanding that life cannot be separated into boxes.”

This report was produced by InfoAmazonia as part of the Collaborative Socio-environmental Coverage of COP 30. Read the original report at: https://infoamazonia.org/2025/11/17/defensores-ambientais-do-sul-global-mostram-por-que-justica-climatica-comeca-com-financiamento/